Liens and lienholders may sound like legal jargon, but they play a vital role in everyday transactions, from buying a home to financing machinery for a business. Understanding these concepts empowers property owners and consumers to navigate obligations, protect assets, and resolve disputes.

What Is a Lien and Who Holds It?

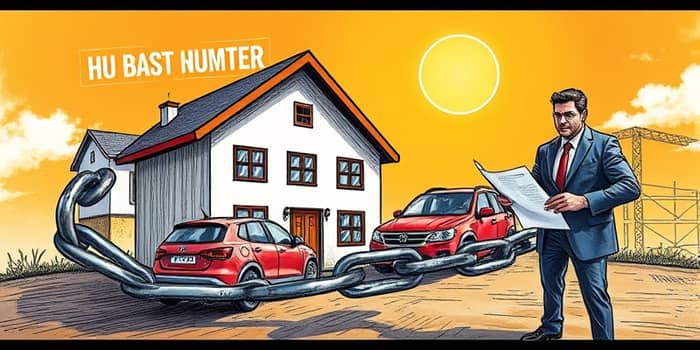

A legal claim or encumbrance on property secures payment of a debt or performance of an obligation. When you sign loan documents for a house or vehicle, you agree to grant a lien, giving the lender a priority right to be repaid from property.

The party that holds this security interest is the lienholder (or lienor). This can be a bank, finance company, private individual, government agency, or even a contractor. The debtor—the borrower or property owner—owes the debt and risks losing clear title to the collateral until the obligation is satisfied.

- Lien: A claim on property to secure debt.

- Lienholder: The creditor holding the security interest.

- Debtor/Borrower: The party that owes the debt.

- Collateral: The asset tied to the lien, such as real estate or vehicles.

Why Liens and Lienholders Exist

Liens serve multiple purposes in commerce and finance. They provide lenders with a robust safeguard against loan default, enabling banks and credit unions to offer large loans—like mortgages and auto financing—at more favorable interest rates than unsecured credit.

By granting a lien, borrowers secure access to capital that empowers businesses to expand and individuals to acquire essential assets. Additionally, liens act as leverage: they can block sale or refinancing of property until debts are settled, incentivizing timely payment and fair dealings.

- Loan security & risk reduction for lenders.

- Facilitates commerce and broader credit access.

- Payment leverage and enforcement of obligations.

- Balance between creditor protection and debtor rights.

Major Types of Liens

Liens come in various forms, reflecting different legal and practical contexts. Below is a summary of the most common types:

Rights and Responsibilities of Lienholders

When a borrower defaults, lienholders can enforce their security interest by foreclosing on real estate or repossessing vehicles and equipment. They also enjoy the right to be paid from sale proceeds first, ahead of junior creditors. In many jurisdictions, lienholders must provide notices, observe timelines, and sometimes obtain court approval before selling assets—ensuring procedural fairness.

Some liens grant possessory rights, allowing creditors to hold physical property until paid. Others require the lienholder to follow judicial procedures for execution sales. These processes underscore the legal balance between enforcing debts and protecting debtor rights.

Consumer Impact: Homes, Cars, Business Assets, and Insurance

Liens directly affect your ability to sell, refinance, or transfer property. On a home, a mortgage lien clouds the title until you pay off the loan, and a foreclosure can damage credit scores.

With vehicles, auto lenders often require essential insurance coverage for collateral, listing themselves as the loss payee on comprehensive and collision policies. If you skip premiums, insurers may notify the lienholder, who can then repossess the car for nonpayment.

Contractors and suppliers rely on mechanic’s liens to secure payment. Property owners should request lien waivers upon payment to avoid unexpected claims that cloud title and block refinancing. Business assets financed through equipment loans carry liens that may restrict sales or leases until debts are cleared.

- Homebuyers: Monitor mortgage balances and title searches.

- Car owners: Maintain required insurance and loan payments.

- Business operators: Obtain lien waivers from contractors.

- Property owners: Check for tax or judgment liens before purchase.

How to Remove or Satisfy Liens

Clear communication and prompt action are key to resolving liens. To remove a lien, you typically:

- Pay the outstanding debt in full or negotiate a settlement.

- Obtain a formal lien release or satisfaction document from the lienholder.

- File the release with the appropriate registry or land records office.

In contested situations, you may pursue a bond to discharge a mechanic’s lien or challenge a wrongful claim in court. Tax liens can often be resolved through installment agreements with authorities. Always keep records of payments and communications, and consider professional advice for complex disputes.

By understanding lien mechanics and proactively managing obligations, you safeguard your property rights, preserve creditworthiness, and ensure smooth transactions. Embrace this knowledge as a tool for financial confidence and responsible ownership.

References

- https://klotzmanlawfirm.com/glossary/lienholder/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ApgqWt-gZAc

- https://blog.nationwide.com/vehicle/vehicle-buying-selling/what-is-a-lienholder/

- https://www.vdm.law/legal-services/civil-litigation-and-debt-collection/liens-and-rights-of-retention

- https://www.boizelle.com/what-is-a-lienholder/

- https://www.crosbyadvisory.com/blog-01/role-lienholder

- https://www.elephant.com/blog/what-is-a-lienholder

- https://cnslien.com/2023/03/24/understanding-lien-rights/

- https://www.thehartford.com/small-business-insurance/what-is-a-lienholder

- https://davisbusinesslaw.com/unlocking-the-mystery-of-a-property-lien-what-you-need-to-know/

- https://www.progressive.com/answers/what-is-a-lienholder/

- https://info.courthousedirect.com/blog/what-is-a-lienholder-and-what-are-their-rights

- https://www.rent.com/blog/dictionary/lien-holder/

- https://www.shipownersclub.com/latest-updates/publications/liens/

- https://www.travelers.com/resources/auto/buying-selling/liens-and-lienholders-explained

- https://www.allstate.com/resources/car-insurance/what-is-a-lienholder